Introduction

Over the last three years the Coastal Restoration Trust has been collaborating with a number of research partners developing methods for monitoring dune vegetation and profiles on our sand dunes. The aim was to provide easy-to-use monitoring guidelines for Coast Care groups, landowners and management agencies involved in restoration programmes on coastal dunes.

Over the last three years the Coastal Restoration Trust has been collaborating with a number of research partners developing methods for monitoring dune vegetation and profiles on our sand dunes. The aim was to provide easy-to-use monitoring guidelines for Coast Care groups, landowners and management agencies involved in restoration programmes on coastal dunes.

The project was funded by the Ministry for the Environment’s Community Environment Fund in collaboration with Coast Care and Beach Care groups, iwi and coastal landowners and with support from our research partners. These included Northland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Greater Wellington and Canterbury regional councils, the Christchurch City Council, Timaru District Council, the Department of Conservation, and Te Kohaka o Tuhaitara Trust in North Canterbury.

These monitoring guidelines along with a data management system are about to be launched on our website.

Monitoring guidelines

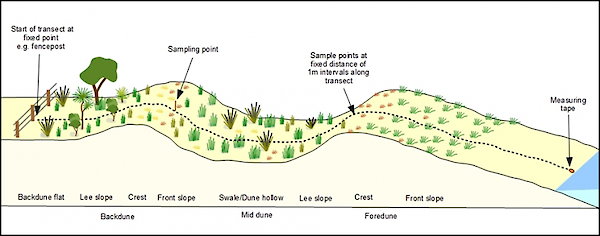

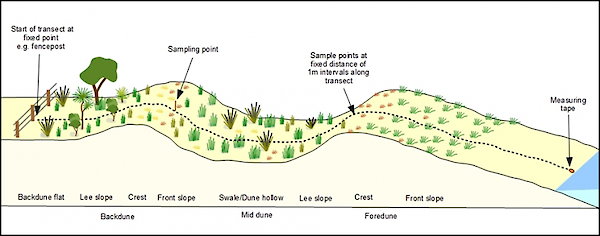

The basis of the dune monitoring method is the use of transects placed perpendicular to the coast sampling across the range of zones from foredune to landward. Key factors surveyed are vegetation cover, species composition and dune profile.

The basis of the dune monitoring method is the use of transects placed perpendicular to the coast sampling across the range of zones from foredune to landward. Key factors surveyed are vegetation cover, species composition and dune profile.

A proven Rapid-Point sampling method is used involving placement of a sample pole at fixed intervals along the transect tape and recording the uppermost species that intersects with the pole at each point.

A practical method has also been developed to map the contour of the dunes that can be matched to the survey of vegetation cover.

Sampling change in vegetation and dune form across these zones will provide an indication of the vegetation types and species in each zone. Re-measurement of these characteristics using consistent methods will show any changes that are occurring over time.

Managing your data

There is no point in accumulating data unless it is used to provide insights into firstly providing a baseline of what the dune and its vegetation characteristics are, and then with repeat surveys providing a meaningful comparison of change over time, especially if active management is occurring.

There is no point in accumulating data unless it is used to provide insights into firstly providing a baseline of what the dune and its vegetation characteristics are, and then with repeat surveys providing a meaningful comparison of change over time, especially if active management is occurring.

The Coastal Restoration Trust in collaboration with Cerulean Design and Development have developed an easy-to-use method for quantifying the vegetation cover and profile of sand dunes that can be undertaken by anyone from coast care groups to management agencies.

The data management system allows users to enter their own data that includes information on the location of their site, GPS locations of permanent landward datum points of each transect, bearing of transects seaward, and then vegetation and dune profile data from point sampling along transects.

Users can manage the entire monitoring operation from setting up dune transects, undertaking the field sampling, entering data into dedicated web-based forms, and viewing results of vegetation cover by species.

Keep an eye out for the launching of this new application that will be freely available on our website.

banded dotterels, Caspian terns, white fronted terns, variable oyster catchers and the occasional little blue penguin.

banded dotterels, Caspian terns, white fronted terns, variable oyster catchers and the occasional little blue penguin.